How to Define a Psychedelic?

Psychedelics, hallucinogens, entheogens, and arguments...

The word psychedelic — meaning mind manifesting/revealing — has become the universal moniker attached to those remarkable consciousness-altering, world-transforming, and self-dissolving drugs we all find so fascinating. Although it’s far from perfect and many don’t like it, it isn’t as if we haven’t at least tried others: Scientists early in the game had a stab at psychotogenic — psychosis inducing — but that was no good, since the psychedelic state is most certainly distinct from psychosis. They also tried psychotomimetic — psychosis mimicking — but that was barely an improvement. Gordon Wasson, Jonathan Ott, Richard Schultes and others proposed entheogen in 1979, but there was no way that a neologism derived from the Greek word for gods could ever be widely accepted by scientists. And it wasn’t. Hallucinogen also had a decent run and remains popular amongst a select few hard-liners, but falls short of being an accurate description of these drugs since few rarely, if ever, induce hallucinations. Psychedelic, imperfect as it is, has stuck.

However, despite being coined by British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond way back in 1957, we still seem to struggle to come to a consensus over which drugs ought to be admitted into the exclusive psychedelic club and which should be refused entry or, having sneaked over the threshold, summarily evicted…

Fortunately, however, the high priests of psychedelic neuropharmacology came to our rescue earlier this year and provided that consensus for us. You can read that consensus here:

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/psymed.2022.0008

Well, you can if you “are a member of a society that has access” to the consensus or are willing to pay $51 for the privilege of reading the consensus.

Upon publication of the consensus, the applause was suitably rapturous:

Yay!! Finally!! Finally, the scalpel of reason and rationality has deftly sliced away all those pesky pseudo-psychedelics and decreed — sorry, reached a consensus — that psychedelics should be defined, and defined only and in perpetuity, as molecules that induce their psychedelic effects via activation of the serotonin 5HT2A receptor.

OK, let’s have a little play with this definition:

So, LSD, which is a 5HT2A agonist and has psychedelic effects, is a psychedelic. Fine. Lisuride, on the other hand, which is also a 5HT2A agonist but does not have psychedelic effects is thus not a psychedelic. Also fine. So far so good. But, what do we mean by “psychedelic effects”? Well, we mean effects elicited by 5HT2A agonists that have psychedelic effects. Or do we? Well, perhaps not. You see, a molecule can have psychedelic effects, but not be a psychedelic (according to their definition). Salvinorin, for example, clearly has psychedelic effects (or does it?) but is not, according to the declared consensus, a psychedelic.

So what is it?

They don’t say. (They don’t even mention salvinorin)

We can resolve this issue of course by simply denying that salvinorin’s effects are psychedelic effects at all — we can call it an “atypical dissociative”. What’s atypical about it? Well, it’s atypical in that, unlike other dissociatives, it has psychedelic effects. Or not. This Tweet clears things up nicely:

More precisely, eh? So, salvinorin is a hallucinogen now? Even though salvinorin doesn’t induce true hallucinations by any formal — dare I say precise — definition? “Write more precisely” indeed. (This was an academic by the way and, despite my mocking tone — I can’t help it — this isn’t really his fault. Modern psychedelic pharmacology, if you’ll excuse the somehow apposite mixed metaphor, has really painted itself into a corner and is tying itself in various nonsensical nomenclatural knots trying to get out of it).

OK, obviously none of this makes any sense and if you’re confused by this point — good. You should be. So, having seen that a consensus requires nothing of the sort, I’ve decided to produce my own consensus.

A consensus of one.

Without the paywall.

There are few different ways to define a drug class. Perhaps the most obvious, and often the most sensible, is to define a drug by its effects or use case. We can also define a drug by its molecular structure or mechanism of action. However, it usually makes more sense to build subclasses of drugs with the same effects/uses but with different mechanisms or molecular families. Antibiotics, for example, can be defined as drugs that either kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria. According to the CDC, there are at least nine subclasses of drugs under the umbrella class of antibiotics: penicillins, macrolides, tetracyclines, and a few more. Each subclass forms a distinct molecular family with its own mechanism of action and tends to be active against different types of bacteria and, yet, all are antibiotics since they all have the same broad effect: killing or inhibiting the growth of bacteria. Antivirals? Same deal. Analgesics? You know it.

So, although there are certainly exceptions, it usually makes much more sense and is generally much more useful to define a drug by what it does rather than how it does it. Subcategories can then be used to distinguish between drugs with different mechanisms of action or from different structural families.

Can we take the same approach with psychedelics?

Would it be so utterly absurd, or imprecise, to accept that any drug with psychedelic effects is a psychedelic, whilst also accepting that different types of psychedelics might elicit their effects via different mechanisms? Seems sensible. And, yet, there appears to be an entirely pointless and (in my opinion) misguided push to at least partially dissociate the definition of the drug from its effects and rely, instead, on its mechanism of action (i.e. 5HT2A agonism). But this merely leads to confusion, as we have seen, by forcing us to either define salvinorin as a non-psychedelic with psychedelic effects or, weirdly, to simply deny or redefine such effects as something else and shoehorn it into a class to which it clearly doesn’t belong. I dare say that if salvinorin had precisely the same subjective effects and yet worked via the 5HT2A rather than the kappa opioid receptor, nobody would be arguing about whether or not it should be categorised alongside the other classic psychedelics. No, the attempt to exclude salvinorin from the psychedelic club (or simply ignore it, as the consensus statement did) isn’t because its effects don’t resemble psychedelics, but simply because of its inconvenient mechanism of action.

However, some might argue at this point that, since we lack a clear and unambiguous definition of “psychedelic effects”, we can’t base a definition of a psychedelic drug on such effects. But is that really true?

Personally, I define a drug as having psychedelic effects if it alters the structure and dynamics of the experienced world and/or the self and/or their relationship to the environment. I’m certainly not saying my definition is perfect or the only workable one — it’s just the one that makes sense to me. Other people might well have very different definitions and, indeed, this is part of the problem. Whilst DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, and 2C-B, for example, are all accepted to be psychedelics, their effects are completely different. A psychedelic drug is like pornography: You can’t define it but you know it when you see it. Fortunately, we don’t have to rely on my definition nor indeed anyone else’s, since we already have several variously validated rating scales that are now routinely used to measure the presence and intensity of psychedelic effects in human subjects. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

Abnormal Mental States questionnaire (APZ)

5-Dimensional Altered States of Consciousness Rating Scale (5D-ASC)

Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI)

Hallucinogen Rating Scale (HRS)

Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ)

Also, several major studies have established what amounts to a “neural signature” of psychedelic effects in humans, including studies of psilocybin, LSD and, most recently, DMT. In all of these studies, the common markers of psychedelic effects are the disruption of major functional networks, such as the DMN (reduction of within-network functional connectivity), with a concomitant increase in communication between networks (between-network connectivity), together indicating loss of network integrity and greater communication between disparate areas of the cortex. Desynchronisation of alpha oscillations and a reduction of alpha power on the EEG are also two of the most consistently observed effects of psychedelics in human studies, reflecting disruption of cortical activity.

See my previous post on Imperial College’s latest DMT neuroimaging study for more details:

Your Brain on DMT...

Recently, Imperial College London’s Psychedelic Research Group, led by Chris Timmermann, published the first major functional neuroimaging study on DMT which, like the previous papers published by the group on both psilocybin and LSD, provide important and novel insights into what’s actually going on in the brain when someone is given this most remarkab…

So, whilst subjective effects between different psychedelics can vary — we’ve still much to learn about this and psychedelic rating scales are far from perfected — we now have measurable and reproducible data on the specific effects of the classic psychedelics on neural activity that distinguishes them from other, non-psychedelic, drugs and which correlates well with the intensity of the quantifiable subjective psychedelic effects as measured by the various rating scales. And, importantly, these effects on neural activity are precisely what one might predict based on the experienced subjective effects. To me, the combination of rating scale and neuroimaging data seems like a solid foundation upon which to build a definition of a psychedelic drug, although it would be premature to insist that a definitive “neuroimaging+rating scale” psychedelic signature is already available — but this is clearly, in my opinion, the direction in which we ought to be headed. However, even at the current state of the art, it’s almost certainly possible for a single well-designed study to relatively easily establish whether a particular drug is psychedelic or not, entirely independent of the mechanism by which it achieves these effects.

Let’s look at ketamine…

On two rating scales — the HRS and the APZ — ketamine scored highly and similarly to DMT when administered as part of the same study (LINK).

The “neural signature” also matches that of the classic psychedelics: Disruption of the DMN, increased communication between networks, and a decrease in alpha power (LINK)

What about salvinorin?

Again, salvinorin scores similarly to DMT on the HRS, in a dose-dependent manner, when compared to Strassman’s initial study in 1994.

What about its neural signature?

"Salvinorin A tended to decrease static functional connectivity within resting- state networks, especially within the DMN, and increase static functional connectivity between these networks.” (Doss 2020) and “a marked increase in delta and gamma waves and a decrease in alpha waves while subjects were under the effect of salvinorin-A.” (Ona 2022).

In other words, the same overall effects observed with the classic psychedelics.

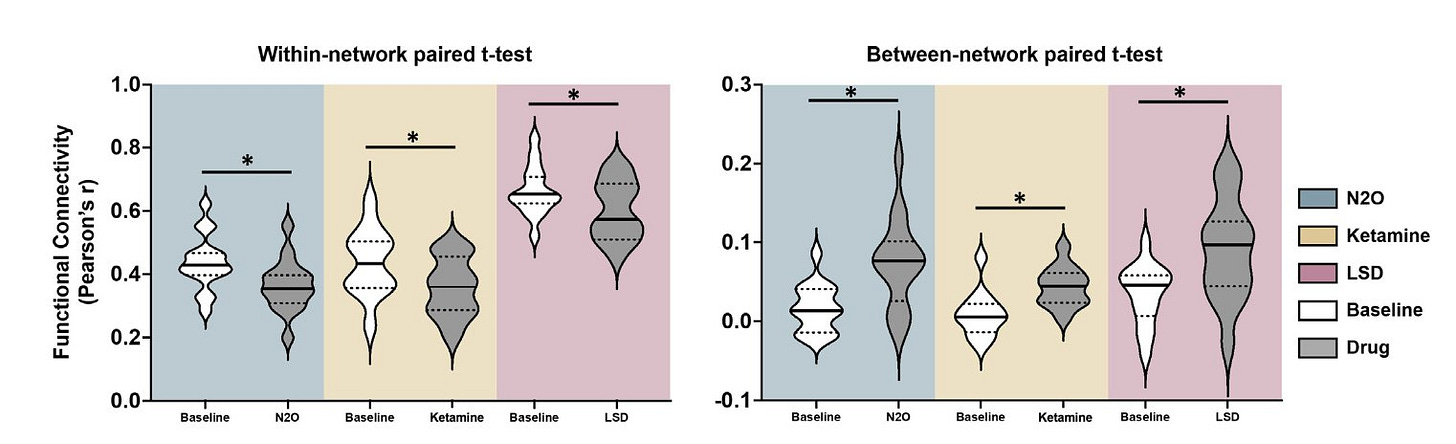

And, a brand new study compared the effects of LSD to both nitrous oxide and ketamine and found the same pattern of network connectivity changes (i.e. decreased within-network and elevated between-network connectivity) (LINK).

The authors state:

“These data suggest the possibility that the psychedelic experience might not track with a single molecular mediator (e.g., 5HT2 receptor) but rather with network-level events that could have a diversity of molecular mechanisms.”

I couldn’t agree more.

So, is ketamine a psychedelic? Yes.

Salvinorin? Obviously.

Nitrous oxide? Yes, seems to be.

And, we can make the same arguments for THC, but I’ll leave you to peruse Pubmed for the details...

OK, but what about the tropane alkaloids (such as scopolamine) from the Old World witching herbs such as mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) and henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) or the New World visionary plants from the Datura and closely-related Brugmansia genera? Well, here we can at least have a considered debate about whether or not they should be defined as psychedelics. Unfortunately, owing to the inherent toxicity of tropane alkaloids, there aren’t any studies (as far as I’m aware) that measured their effects at psychoactive dosages using any of the psychedelic rating scales, nor using neuroimaging techniques. So, we can neither confirm nor deny their status as psychedelics, according to our — sorry, my — new consensus (of one) definition. And this is fine. Fortunately, unlike the other psychedelics, the tropane alkaloids do reliably induce true hallucinations: non-veridical perceptions that appear indistinguishable from normal perceptions, as differentiated from the open and closed eye visuals that announce themselves as such, as elicited by psychedelics such as DMT. So, we can quite happily and without confusion or ambiguity call the tropanes hallucinogens — hallucination inducing. Others prefer deliriant — inducing a state of delirium — which might also be acceptable.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that a drug defined as a psychedelic must elicit only psychedelic effects — many drugs fall into more than one class. Fluoxetine (Prozac), for example, is both an antidepressant and an anxiolytic. Sildenafil (Viagra) is both an antihypertensive and… well you’re well aware of its other use. MDMA is often referred to as an empathogen, owing to its pro-social effects. But it’s also a stimulant and, yes, it’s also a psychedelic, since its effects on neural activity are “almost identical to the results previously reported for hallucinogenic drugs,” including decreased connectivity within the DMN (LINK). MDMA also scores similarly (but at a lower intensity) to both psilocybin and ketamine on the Altered States of Consciousness Rating Scale. And, ketamine, of course, is not only a psychedelic (mainly exhibited at lower doses), but is also a dissociative anaesthetic (at higher doses).

So, after all that, here we have the consensus (of one):

The Typical Psychedelics (i.e. 5HT2A agonists).

LSD

Psilocin

N,N-DMT

5-MeO-DMT

2C-B

MDMA…

And any other drug that has psychedelic effects (measured using a combination of rating scale and neuroimaging data) elicited primarily via 5HT2A receptor agonism.

The Atypical Psychedelics.

Ketamine and its psychedelic analogues, such as PCP

The salvinorin family

Nitrous oxide

THC and related analogues

(Tropane alkaloids and muscimol — as yet unconfirmed. Perhaps another class entirely, such as hallucinogen or deliriant)

And any other drug that has psychedelic effects not elicited primarily by 5HT2A receptor agonism.

Of course, we can form subclasses based on structure or mechanism of action, just as we do with other drug classes. But I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader…

While I agree with you most of this nomenclature-based gatekeeping is ridiculous, I'm not sure your biological metrics for psychedelics have enough discriminant validity.

If you give SSRIs to "healthy" volunteers, acutely, we see the same changes: Decreased within-DMN rsFC (Van Wingen et al., 2014) and reduced alpha (Dumont, De Visser, Cohen, & Van Gerven, 2005). I'm sure you're aware of the criticisms surrounding Carhart-Harris et al. in their global connectivity analysis to differentiate Lexapro from psilocybin responses...so that may not be of much use either unless repeated under more rigorous settings.

One might undoubtedly argue then, clearly SSRIs can be differentiated by subjective inventories..but I would suggest that places us right back in the pornography realm. To me, the only value in having this masturbatory nomenclature exercise is to enhance descriptive validity of biological function for these substances.

I don't think alpha and DMN approach antibiotics in that regard.

Psychedelic is about effects, not about a way to achieve those effects. And there are many ways - via 5-HT2A, via NMDA, via Kappa-Opioid, via some obscure ways (cannabis), and even via meditation/breathing practices.