Kambo: The Complex Pharmacology of the Amazonian Giant Monkey Frog

Vomiting. Lots of vomiting...

If you spend any time with a reasonably psychedelic crowd, it’s hard not to catch a whiff of kambo on the air — the Amazonian frog ritual that’ll have you bent double and red-faced, filling buckets with convulsive jets of watery vomit whilst spraying the walls in the opposite direction. It’s all about the purge, man. The last psychedelic conference I attended, I dare say every third person I spoke to was either planning a kambo session in the near future or proudly displaying the stigmata of rituals past. It is, as they say, all the rage.

I must admit I’ve neither tried kambo myself nor do I have any particular interest in this kind of chemical trial by ordeal. “It’s very humbling.” I was once assured by an American aficionado. “It’s really not my bag,” was all I could offer in reply, sipping on a well-milked cup of British Builder’s Tea — pinky raised in the proper fashion. Those keen on kambo will often make claims as to its benefits ranging from the plausibly vague to the less plausibly specific: second-hand anecdotal reports of cancer remission, restored vision, and recovery from Alzheimer's can be found. However, I make no judgements about these claims and, as always, whatever the benefits or risks might be — and we’ll certainly get to those — it’s the pharmacology that gets my attention. And the pharmacology of kambo is as fascinating as it is complex.

The skin secretions of the Giant Monkey Frog, Phyllomedusa bicolor, have been used for centuries by natives of the Western Amazon in shamanic healing and purification rituals, to strengthen the body and mind, and to improve sexual performance. The frogs are collected at dawn, following their distinctive call, before being stretched on crossed branches and gently poked to stimulate their skin secretions, which are then scraped onto wooden sticks for later use. The frogs are then released to croak another day, baffled but largely unharmed.

To perform the ritual, from two to more than 100 burn points are made on the skin — usually the arms, chest, or back of the leg — using a thin vine called titica, and the kambo secretion applied to these points. The effects begin within a couple of minutes and usually include severe convulsive vomiting, diarrhoea, tachycardia (a racing heart), a sharp drop in blood pressure, anxiety, and intense sweating. These acute effects usually subside within an hour and are followed by a more tranquil state that incudes drowsiness, dizziness, and euphoria. Many kambo users report a prolonged “afterglow” state that can last a week or more, with increased strength and stamina, a sharper mind, and a reduction in chronic pain.

Here’s a video showing the whole process:

The pharmacology of kambo is complicated: its rich chemistry and varied pharmacology make for a complex pattern of physiological effects. More than 20 bioactive peptides have been isolated and characterised from the Phyllomedusa bicolor frog’s skin secretions and it’s likely many more remain to be discovered. Having said that, the overall effect and, in my opinion, the likely major source of its benefits lies in kambo’s powerful ability to both mimic the human stress response whilst simultaneously generating an actual highly unpleasant and stressful experience.

First though, a word about peptides: All proteins are technically polypeptides — chains of the 20 naturally-occurring amino acids, with chain lengths varying from around 50 to 34,000 amino acids (this record goes to titin, an important structural component of your muscles). Peptides shorter than 50 amino acids are referred to as oligopeptides, and the bioactive peptides in the kambo secretions fall into this category. Although their structures look fiendishly complicated, they are pretty easy to construct (compared to many alkaloids for example), since their manufacture simply requires the stitching together of amino acids in a particular order. For a frog, this is no more difficult than making that bead necklace you wear to all your kambo ceremonies with your other San Francisco-based media strategist friends.

The oligopeptides in the secretions of the kambo frog can be grouped into about 10 categories depending on their biological activity. I won’t discuss them all, since only a handful are likely relevant to the acute and delayed effects of the kambo ritual:

Phyllocaerulein.

Sauvagine.

Phyllokinin.

Deltorphins and demorphins.

The most prominent bioactive peptide in kambo is phyllocaerulein, a 9-amino-acid peptide that mimics the endogenous human bio-peptide cholecystokinin, which stimulates gut motility, as well as gastric and pancreatic secretions (link). High levels of cholecystokinin (or phyllocaerulein) also induces nausea, vomiting, and anxiety (link). As such, even if the kambo secretion contained only phyllocaerulein, you’d still be in for a pretty rough time. But the kambo frog has a few more peptidic tricks up its….. do frogs have sleeves? Anyway, let’s hop on…

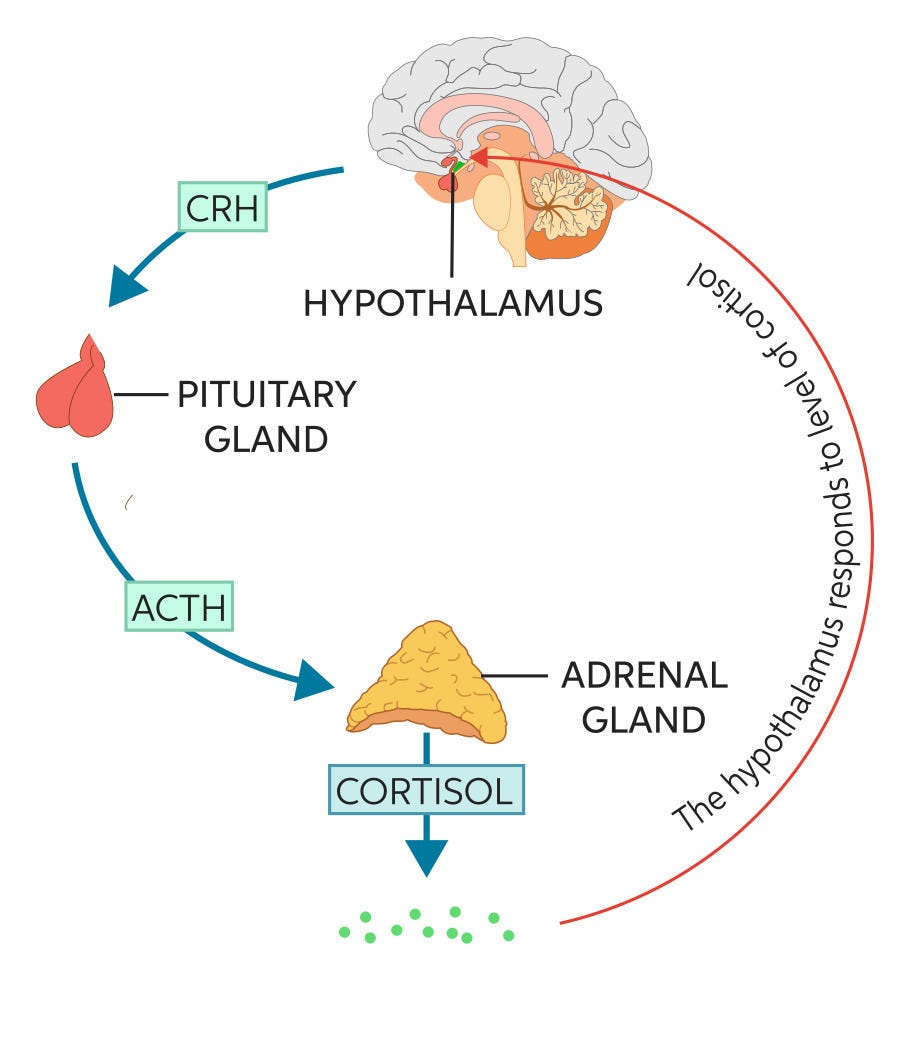

The next important kambo component is sauvagine, a 40-amino-acid peptide that mimics human corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), a 41-amino-acid oligopeptide released by the hypothalamus and a primary driver of the human stress response, stimulating the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland, which in turn stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol (this forms the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis) (link).

Together with adrenaline, cortisol forms the hormonal arm of the fight-or-flight response: Cortisol increases glucose in the bloodstream (and enhances its use by the brain), promotes the metabolism of fats, and increases the availability of substances that repair tissues. CRH can also promote the release of serotonin in the gut, which causes vomiting by activation of 5HT3 receptors (the anti-vomiting drug ondansetron is a 5HT3 receptor antagonist), as well as increasing alertness and anxiety levels by activating CRFR2 receptors in the brain. So, overall, sauvagine is mimicking your body’s endogenous hormonal response to threatening stimuli (such as a predator) in the absence of an actual threatening stimulus, preparing your body and brain to either neutralise the threat, run in the opposite direction or, in the case of kambo, simply shit yourself.

Finally, at least in terms of the unpleasant effects, we have phyllokinin, an 11-amino-acid kambo peptide that mimics human bradykinin but is much more potent (link). Bradykinin is a 9-amino-acid oligopeptide released from mast cells as part of the inflammatory response. It causes relaxation of vascular smooth muscle, causing blood vessels to dilate and blood pressure to drop. It also elevates heart rate, as well as sensitising certain types of pain receptors (increasing sensitivity to painful stimuli).

Phyllokinin has the same effect and is partly responsible for the acute drop in blood pressure, flushing, and dizziness of kambo, adding an extra dimension to the purgative effect, and supplementing the effects of sauvagine.

OK, now to the nice peptides...

The endorphins are the body’s “natural opioids”, released by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, and also form part of the stress response: they decrease the sensation of pain and increase the feeling of well-being by stimulating opioid receptors. There are three main endorphins produced by humans: α-endorphin (16 amino acids), β-endorphin (31 amino acids), and γ-endorphin (17 amino acids). The kambo frog produces a handful of peptides that mimic these endogenous human endorphins: the deltorphins and demorphins. These have potent analgesic (pain-relieving) and euphoric activity. The deltorphins, in particular, are around 4,000 times more potent than morphine (link).

So, we can begin to see what’s happening following a kambo treatment: the nausea and intense vomiting caused by phyllocaerulein is, in itself, highly unpleasant and stressful. Sauvagine and phyllokinin further increase the stress by causing blood pressure to plummet, pushing up the heart rate, whilst also elevating anxiety levels. All in all, this amounts to a pretty awful experience. This is a feature, not a bug. Whilst excessive and chronic stress is harmful, brief periods of stress enhance neural function and may even promote the growth of new neurons. For example, rats exposed to an acute stressor display enhanced cognitive performance two weeks later, driven by the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus. This could also be achieved by injecting the rats with the major stress hormone corticosterone (the rat equivalent of cortisol) (link).

According to Daniela Kaufer, associate professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley:

“Some amounts of stress are good to push you just to the level of optimal alertness, behavioral and cognitive performance.”

So, the perceived benefits of kambo can be explained by its ability to create a highly stressful, but relatively brief, physiological and psychological state. Once these acute effects begin to subside, it’s plausible that the endorphin-mimicking deltorphins and demorphins mediate the feeling of well-being and the reduction in chronic pain during the kambo afterglow.

Any effects beyond this are largely speculative. Although the kambo frog also contains a range of antimicrobial peptides, known as the dermaseptins and which protect the frog from pathogenic skin micro-organisms in the damp rainforest environment, it isn’t clear whether they are present in sufficient concentrations to mediate any kind of antibiotic, let alone anti-cancer, effect (link). Whilst several of the dermaseptins have been shown to have anti-tumour properties (link), the presence of these peptides is far from establishing their clinical significance in humans at the concentrations absorbed during a typical kambo ritual.

All in all, there is a fairly robust evidence-based rationale for thinking that kambo can have beneficial effects on cognition and overall well-being, although some of the other claims lack evidence. However, having beneficial effects doesn’t mean risk-free. Rupture of the eosophagus (caused by the intense vomiting), acute kidney failure, liver damage, psychosis, and even death, have been reported in the medical literature, which you can explore at your leisure here:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214750022000865

If you do intend to give the frog a go, it’s probably a good idea to let someone with extensive experience take charge, rather than purchasing kambo sticks online and performing the ritual alone in your back garden. But you do you. As the world’s most famous kambo frog, Kermit, once said, "Life’s like a movie. Write your own ending.”

Nope. This is one substance I’ve never felt called to try. A friend of a friend died doing Kambo in West Palm Beach, FL. He was alone.

But this is fascinating. It reminds me of a study I read about how people suffering from anhedonia induced by sobriety could be treated by putting themselves in uncomfortable or high-adrenaline situations, like having them act abnormal in public or sky diving etc.

The portrayal of how kambo is obtained does not reflect the true reality of a cruel and painful (for the frog, at least) process that sometimes involves placing the frog over an open fire in order to stimulate skin secretions. Kambo users should perhaps consider an alternative to torturing frogs - a day of pseudo-crucifixion. What incredible hypocrisy that we continue to believe that we can attain spiritual healing though the heartless exploitation of the Sonoran Desert toad (5-MeO-DMT) and the Kambo frog.