Brief Primers on the Neuroscience of Psychedelics 1: The Classics

Why is psilocybin (or LSD or mescaline) psychedelic?

Whether you’re awake, dreaming, or in a peak psychedelic state, your experienced world, and indeed the model of yourself as distinct from the environment, is always a model constructed by your brain as a pattern of neural activity. When you ingest a psychedelic, it is the structure and dynamics of this world and self model that changes. But how and why?

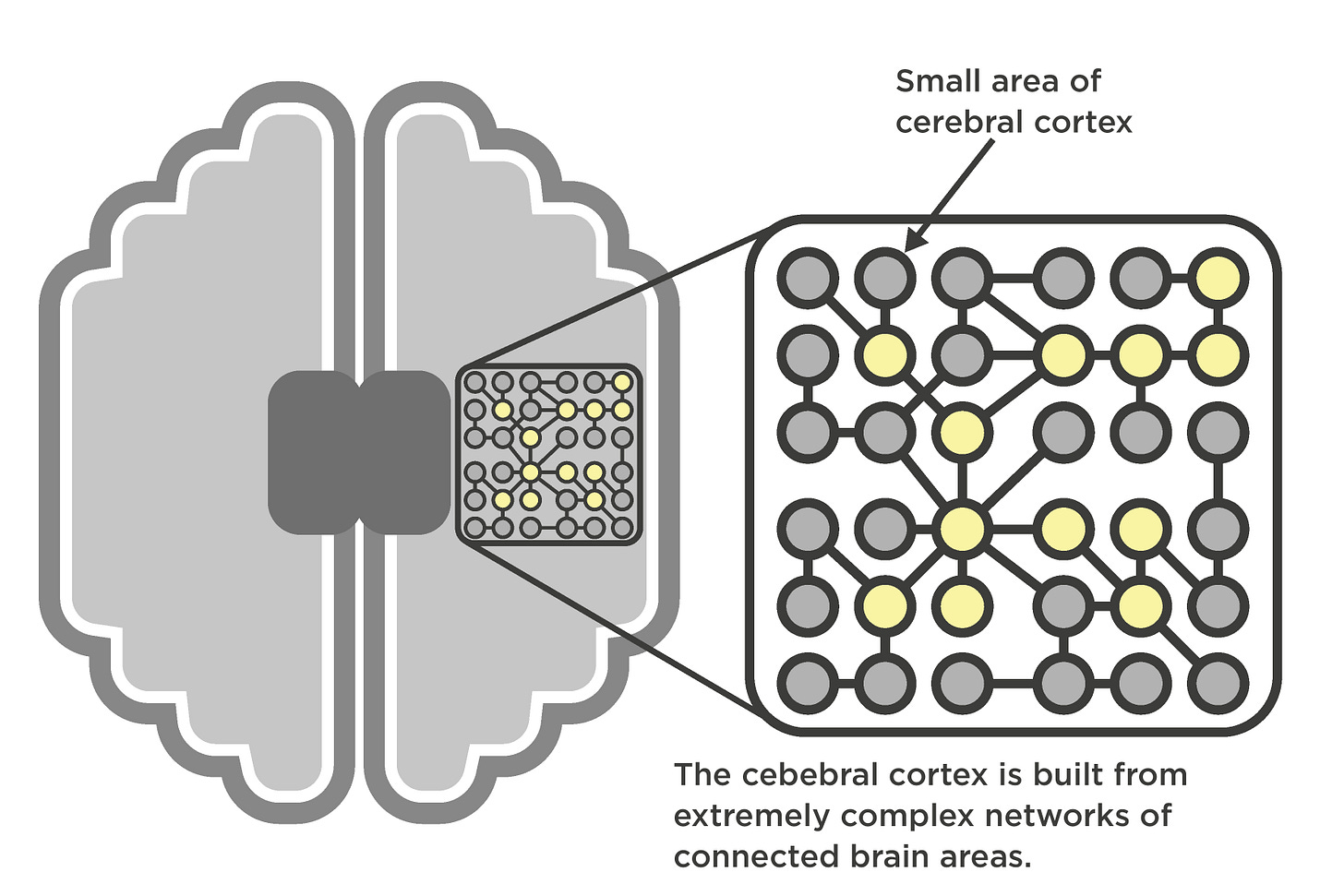

Your cortex is constructed as a mosaic of closely packed cylindrical structures built from neurons — these are your cortical columns, each forming a very small area of the cortex.

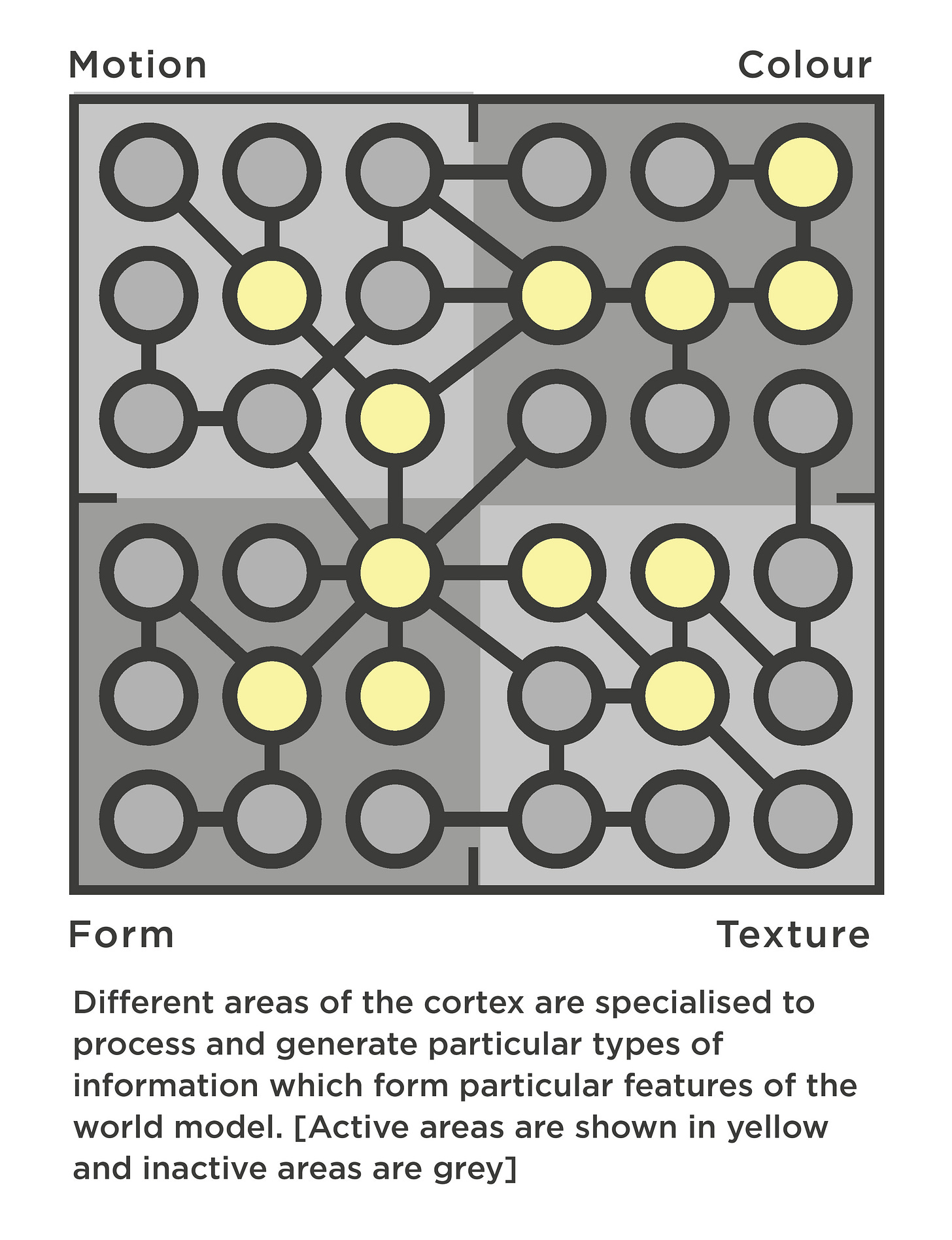

The columns are specialised and tuned to receive, process, and generate patterns of information that correspond to particular features of the world, such as lines, colours, textures, objects, and movement. Although something of an oversimplification, it’s instructive to think of each column as being either active (“on”) or inactive (“off”), with the pattern of column activation representing all the features of your world at any particular moment.

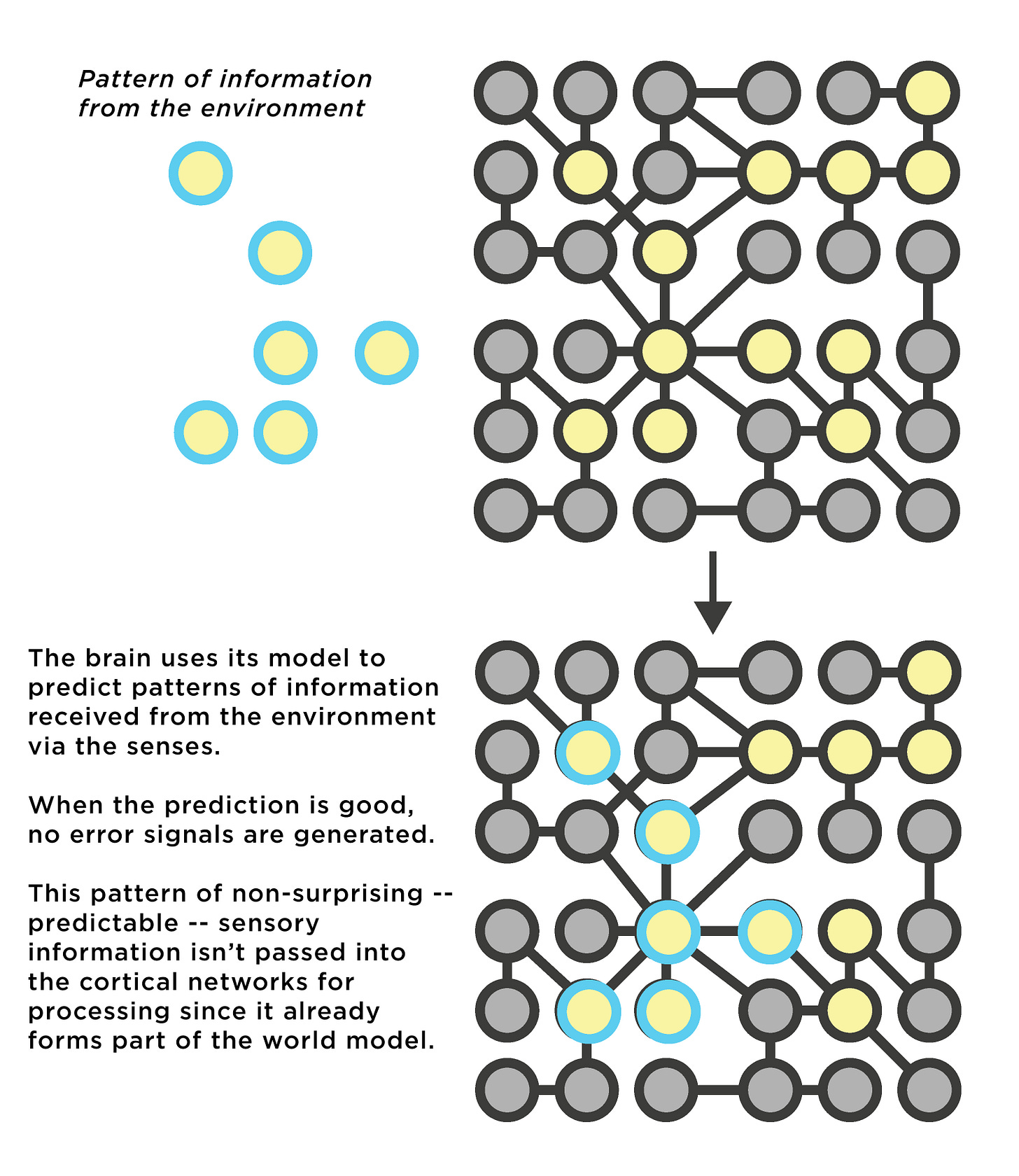

The cortical columns are connected, using synapses, to form networks that control the structure and flow of information through the brain, allowing it to “sculpt” its model of the world. By modifying these patterns of connections throughout the course of evolution, development, and experience, the brain improves and refines this model. The world you experience from moment to moment is the highly complex pattern of information sculpted by these networks of columns. Your brain evolved to generate your world as a model of the environment, and constantly tests its model against incoming sensory information by attempting to predict the patterns of sensory information entering the brain (“If the model I’m using is good, what should I expect to happen next?”). If the prediction is successful, then that sensory information is suppressed — filtered out — meaning it isn’t passed into the networks of the brain for further processing. It doesn’t make sense for the brain to process sensory information that’s already part of the model because, in a way, that information is already known.

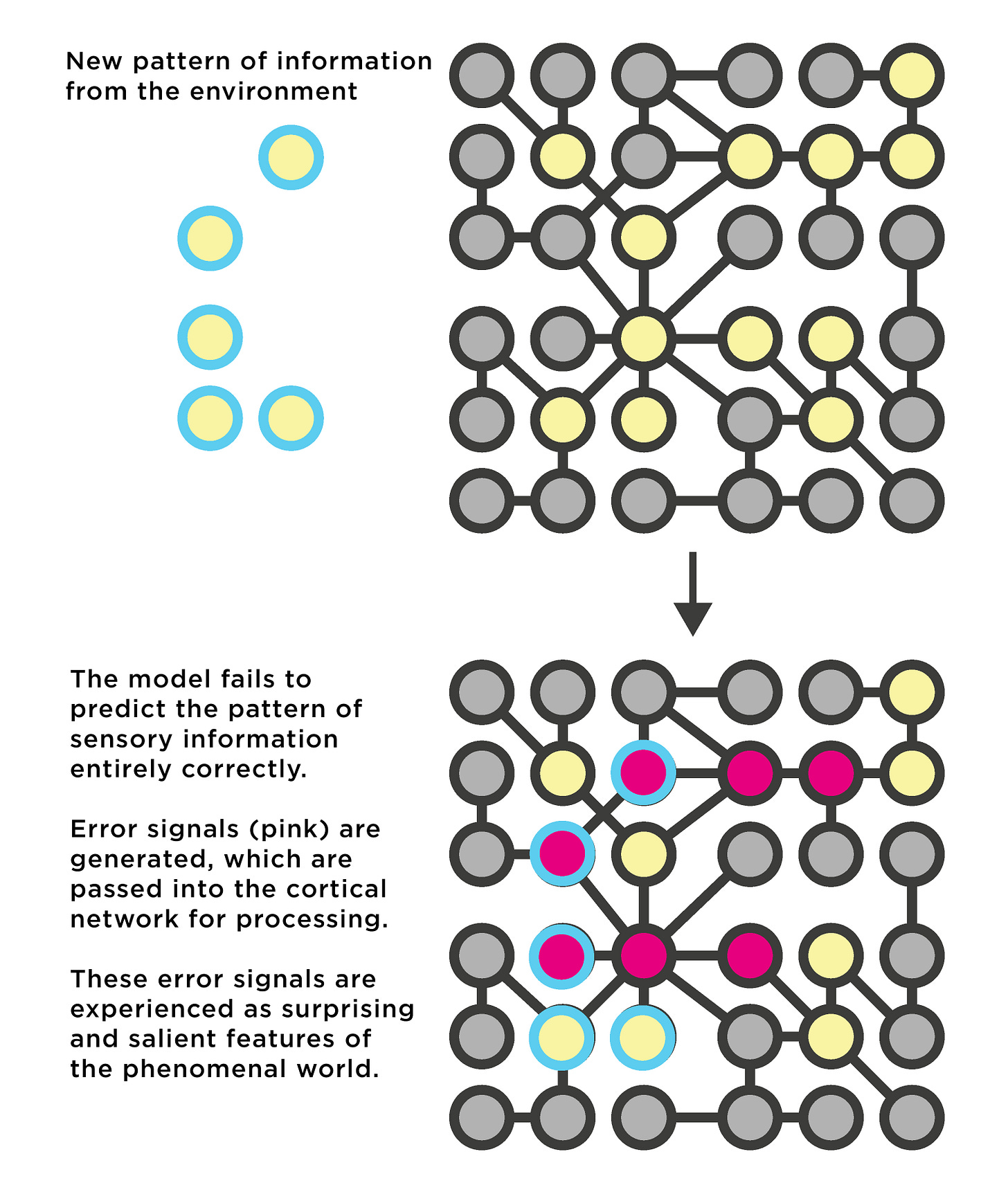

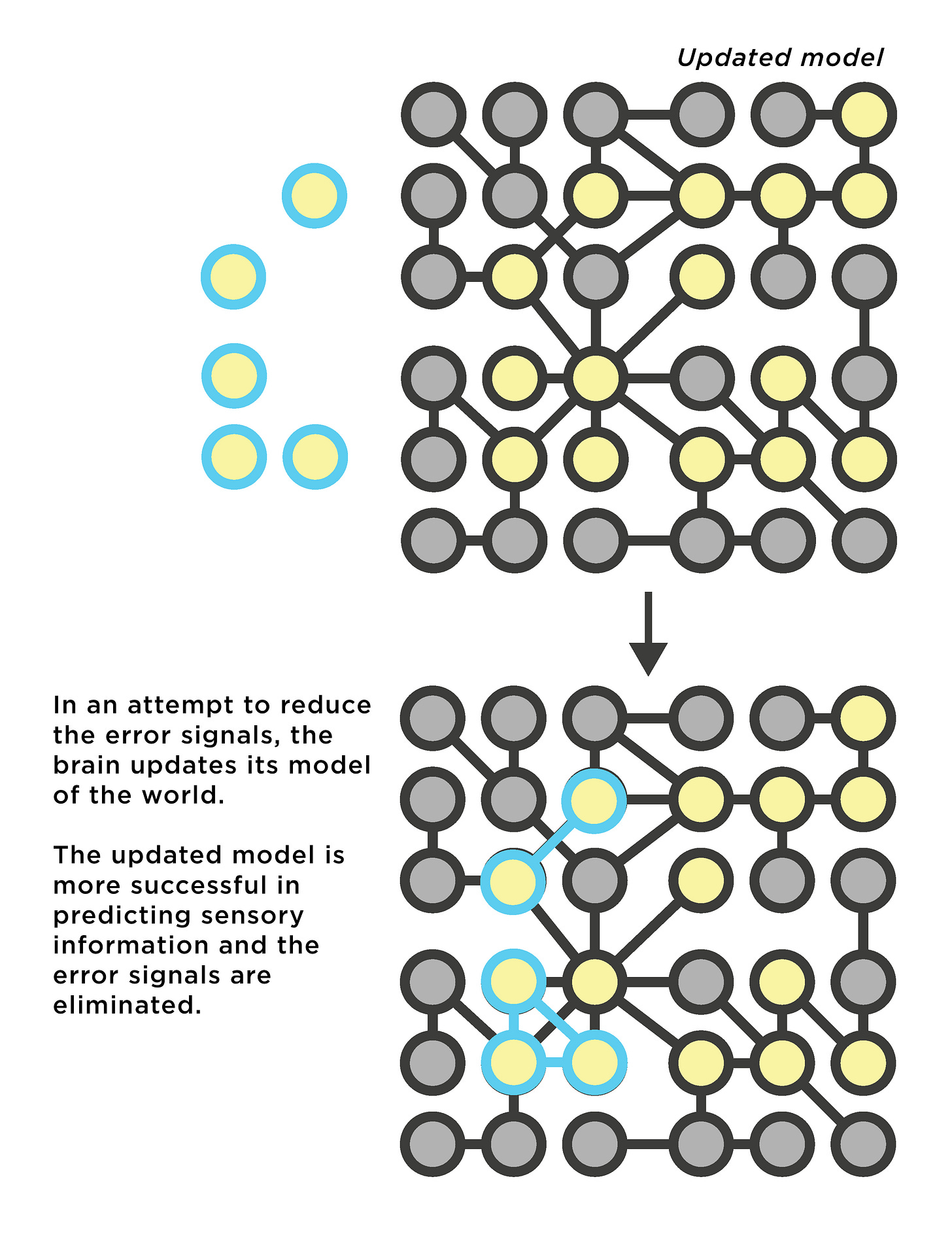

However, if unexpected and surprising patterns of sensory information are received — if model predictions fail — then error signals are generated, which are then passed into the cortical networks…

These prediction errors are used as a kind of training signal to update the model until the errors are reduced.

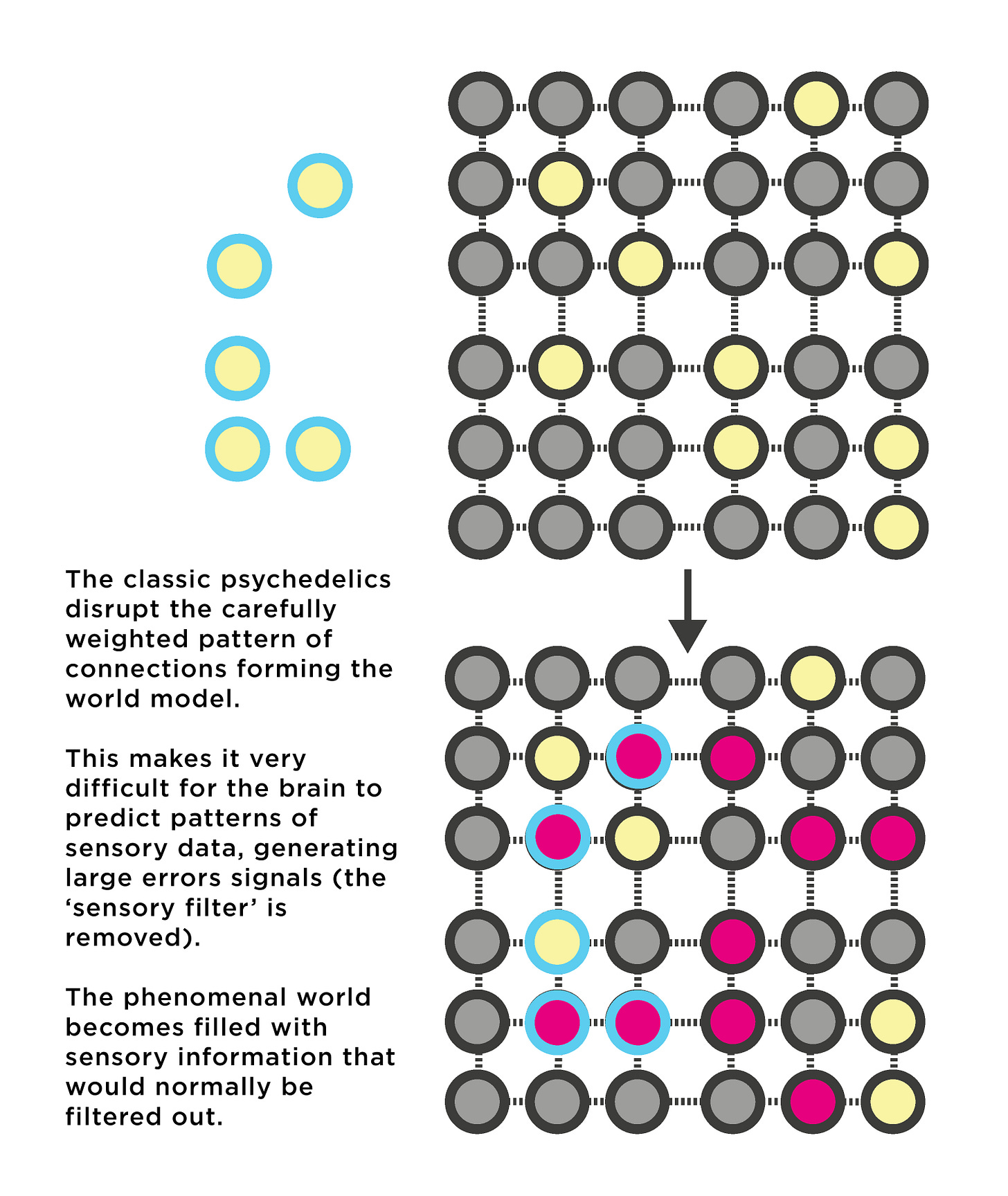

The classic psychedelics (psilocybin, LSD, mescaline, etc) exert their effects principally by binding to a specific type of serotonin receptor — the 5HT2A receptor — heavily expressed in the deep layers of the cortical columns. Upon binding to this receptor, these psychedelics stimulate the neurons in these layers, making them much more responsive to incoming signals from other neurons and much more likely to fire signals that are then passed to other neurons via their synaptic connections. The overall result is a highly excitable layer of neurons over large areas of the cortex, with information flowing much more freely between cortical columns.

Since the brain’s ability to construct a coherent model of the environment relies on a delicately constructed pattern of weighted connections between cortical columns, this information free-for-all disrupts or “shakes up” the world model. When research volunteers are given a psychedelic and placed in an MRI machine, normally well-ordered patterns of brain activity are seen to breakdown as information begins to flow out of formerly well-demarcated networks, and networks that were once disconnected begin speaking to each other. From the perspective of the psychedelic user, the world undergoes a distinct shift from being stable and predictable to being unstable, fluid, and unpredictable.

Naturally, this disrupted model becomes less successful at predicting sensory information, which leads to an increase in error signals flowing through the networks of the cortex. Recall that the brain filters out the sensory information it correctly predicts, with only the unpredicted and surprising information being processed in the form of error signals. By disrupting the brain’s ability to predict sensory information, psychedelics effectively remove this filter and information that would normally be filtered out suddenly fills the world and everything becomes surprising, salient, and novel.

In his visionary classic, The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley eloquently describes this state whilst gazing at a bunch of flowers:

“He could never, poor fellow, have seen a bunch of flowers shining with their own inner light and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged; could never have perceived that what rose and iris and carnation so intensely signified was nothing more, and nothing less, than what they were - a transience that was yet eternal life, a perpetual perishing that was at the same time pure Being, a bundle of minute, unique particulars in which, by some unspeakable and yet self-evident paradox, was to be seen the divine source of all existence.”

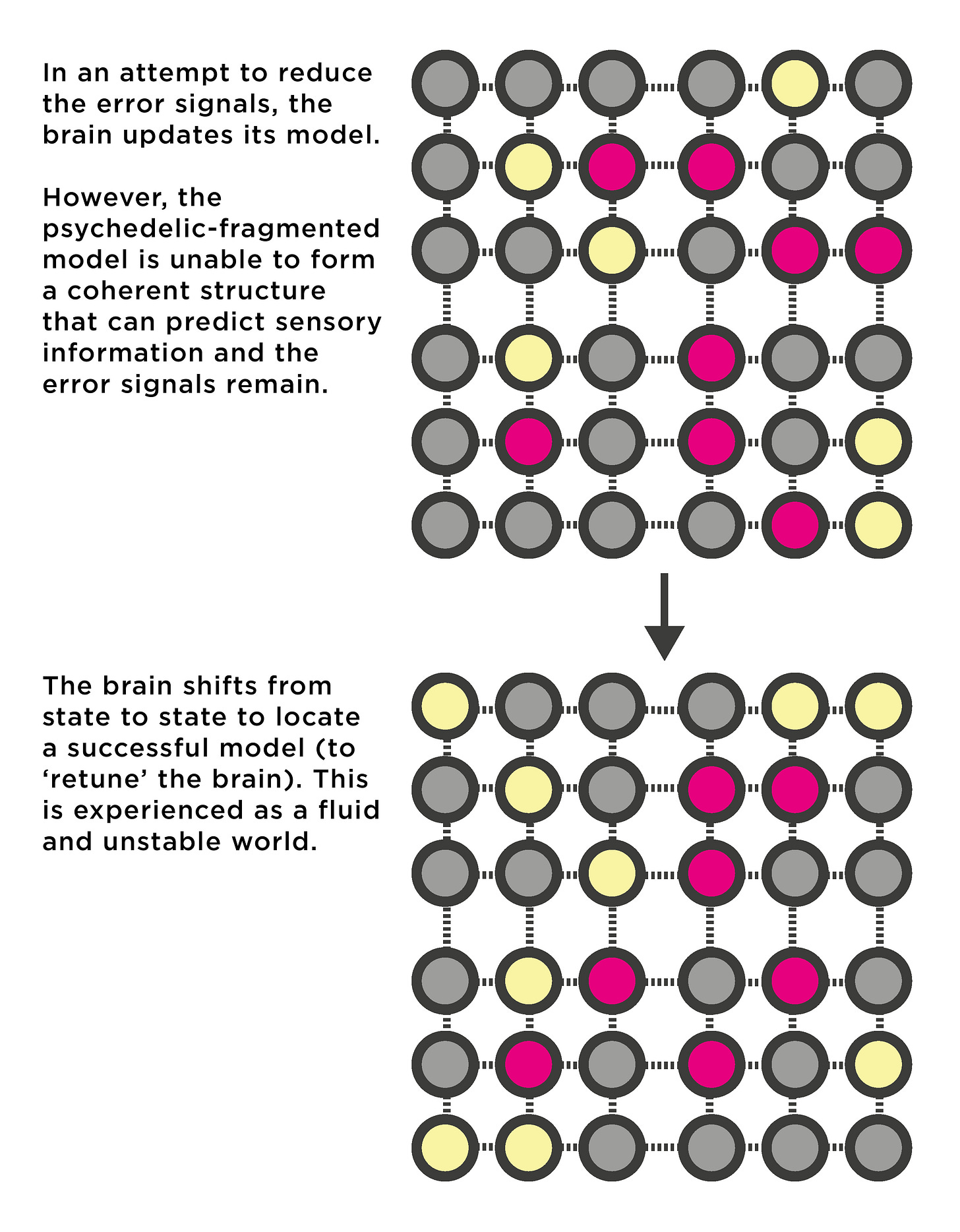

Overall, the brain loses its grip on the flow of information both into and through itself. And, naturally, it attempts to correct the situation by updating its model — as it would under normal circumstances when error signals are generated — but it’s unable to form a stable and coherent model which reduces the error signals. As such, it continues searching, updating, and the subjective world becomes unstable, shifting rapidly in response to the unfiltered barrage of information from the environment. It’s as if the brain has been nudged out of tune and is fumbling with the dial attempting to retune itself. From the tripper’s perspective, the world becomes fluid and unstable: everything moves and flows, objects merge or change their identity from moment to moment.

Legendary psychedelic chemist Alexander Shulgin describes this effect during a mescaline trip:

“I sat there on the seat of the car looking down at the ground, and the earth became a mosaic of beautiful stones which had been placed in an intricate design which soon all began to move in a serpentine manner. Then I became aware that I was looking at the skin of a beautiful snake — all the ground around me was this same huge creature and we were all standing on the back of this gigantic and beautiful reptile"

Of course, it isn’t only the experienced world “outside” that is altered by the classic psychedelics: The sense of self and the relationship between that self and the environment also begins to change and break down. This is often referred to as ego death. That lose conglomeration of concepts that defines you begins to unravel and you become nothing more than a pure point of awareness, without boundaries, without a clear demarcation between the self and the environment.

This self model isn’t completely understood (and many would argue that it never will be, but that’s more of a philosophical problem), but we know that this self model is likely instantiated in some of the higher-order networks (networks of networks) in the cortex. The default mode network (DMN) is a critical component of a set of large scale networks that represent this “self/ego” model distinct from the environment model.

Neuroimaging studies reveal how these high-order networks, including the DMN, also begin to break down under the influence of the classic psychedelics, and with it the sense of self and the distinction between the self model and the environment. Networks that were once well-defined and demarcated become fuzzy, their boundaries dissolve, and one is no longer aware of the distinction between the self and the other. This experience is often referred to as oceanic boundlessness — an overwhelming sense of merging, or becoming “one”, with the world or, indeed, the entirety of existence itself, when distinctions between what is self, what is other, the inside and the outside, dissolve and, perhaps, reveal themselves to be entirely illusory and, for as long as the drug effect persists, of little concern.

For a much more detailed discussion and explanation of the neurological mechanisms behind the classic psychedelics, please refer to my latest book, Reality Switch Technologies: Psychedelics as Tools for the Discovery and Exploration of New Worlds, which covers all the major classes of psychedelics in unprecedented depth and detail. See my website for more details:

https://www.buildingalienworlds.com/books.html

What if I said everything you just described was also a model - neurons and all, and that all we have are models of models?

What if there is nothing outside of the models?

Or if all science is done within the model (neurons, labs and all), and we can't ascribe causality to it, then where does the causality lie?

"The cortical columns are connected, using synapses, to form networks that control the structure and flow of information through the brain, allowing it to “sculpt” its model of the world."

But the cortical columns are also the model.

Isn't it like saying the characters in a film wrote the script?

Is anyone in neuroscience working out a way to talk about this stuff but without ascribing causality to the observed brain functions?

great read, loved it. i wonder which mechanisms shift perception during meditation.

as one goes through the states, there is a successive ceasing of mental activity and fading of the ego and dualistic worldview.

its being replaced by awareness itself, which also starts to fade in the eigth jhāna and everything gets very dreamy and trippy when the mind stops forming perceptions altogether. you cannot tell if you are awake or dreaming at this point.